- Worship

- Education

- Lifecycle

- Events & Programs

- About Us

- Join Us

- Donate

Rabbinic Mission to the South 2023

Rabbinic Mission to the South 2023

Day Five – February 2

Our last stop today was at the Peace and Justice Memorial Center, a moving memorial to the more than 4,400 Blacks who were lynched by groups of at least 2 or more between the years 1877-1950. More than 10,000 Whites are documented as having participated in a lynching (most were never punished in any way for their crimes), but it was even more pervasive than that. Some of the memorial panels told of lynching events in which 5,000, 10,000, or even 15,000 individuals gathered to witness the horror. As another panel indicated, lynchings “were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynchings were targeted racial violence perpetrated to uphold an unjust social order.”

This is a story that still needs to be told. Growing up in Atlanta, I learned the story of Leo Frank, a Jewish businessman from New York who was falsely convicted of murdering a young female employee in his Atlanta pencil factory. Shortly after Frank’s sentence was commuted from the death penalty to life in prison, a White mob stormed the prison where Frank was being held, drove him more than 3,000 miles to Marietta (a place that today has a very strong Jewish community), and hanged him from a tree. Post cards were produced with pictures of the crowd gathered to witness this savagery.

Every Jew from Atlanta knows the story of Leo Frank. Many of us saw the musical about Leo Frank, “Parade,” when it was shown at Fords Theater in Washington. The horrors of Frank’s trial and lynching led to the establishment of the Anti-Defamation League. We rejoiced in 1986 when Frank was granted a posthumous pardon. But that was just one person. 4,400 lynchings over a period of 73 years. … I can only imagine the fear such events inspired among ordinary Black citizens at the time. Our people knows horror; our people knows terror; we need more of these stories to be told.

The memorial included stones listing the names of individuals who had been lynched, sorted by county. It was painful to learn of the four lynchings that had taken place in Dekalb County, Georgia, where I was born and raised. May the memories of Reuben Hudson, Jr., Porter Turner, unknown victims in DeKalb County, and so many others be a blessing. May the stories of these horrors not be told in vain.

There is so much more to process and so many more stories to tell. I look forward to mentioning a few thoughts about this powerful mission at services on Shabbat, and in the weeks and months to follow

Day Four – February 1

Our theme for today was courage.

We began our day in the home of Dr. Valda Harris Mongtomery. In the 1950s and 60s, this home had been used as a “safe house” for Freedom Riders as they strategized for a trip to Jackson, Mississippi and other actions. We met there with Dr. Bernard LaFayette, a leading organizer who trained the movement in principles of nonviolent confrontation. He instilled in his pupils the courage to resist reacting even to the most heinous of violent provocations. LaFayette described how as a school principal, he turned gangs into social clubs. He organized sprots clubs and cheerleading squads, and trained them to become members of the movement.

We began our day in the home of Dr. Valda Harris Mongtomery. In the 1950s and 60s, this home had been used as a “safe house” for Freedom Riders as they strategized for a trip to Jackson, Mississippi and other actions. We met there with Dr. Bernard LaFayette, a leading organizer who trained the movement in principles of nonviolent confrontation. He instilled in his pupils the courage to resist reacting even to the most heinous of violent provocations. LaFayette described how as a school principal, he turned gangs into social clubs. He organized sprots clubs and cheerleading squads, and trained them to become members of the movement.

We then moved to Birmingham, where we visited the 16th Street Baptist Church. We met with Dr. Carolyn McKinstrey, who was present in the church when it was bombed on the morning of September 15, 1963. McKinstrey suffered post-traumatic stress in the years after that attack; she had walked past the bathroom where the blast occurred—killing four innocent girls—just moments before it occurred. For a long time, McKinstrey didn’t talk about that terrible event. But on the occasion of the 25th commemoration, she raised money to commission a memorial sculpture to the victims of that bombing—14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and 11-year-old Cynthia Wesley—together with Virgil Ware (age 11) and Johnny Robinson (14) who died in separate incidents on that same day. At the time of the church bombing, there were already 60 other unsolved bombings in Birmingham that year, a fact that led the city to be dubbed “Bombingham.”

We then moved to Birmingham, where we visited the 16th Street Baptist Church. We met with Dr. Carolyn McKinstrey, who was present in the church when it was bombed on the morning of September 15, 1963. McKinstrey suffered post-traumatic stress in the years after that attack; she had walked past the bathroom where the blast occurred—killing four innocent girls—just moments before it occurred. For a long time, McKinstrey didn’t talk about that terrible event. But on the occasion of the 25th commemoration, she raised money to commission a memorial sculpture to the victims of that bombing—14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and 11-year-old Cynthia Wesley—together with Virgil Ware (age 11) and Johnny Robinson (14) who died in separate incidents on that same day. At the time of the church bombing, there were already 60 other unsolved bombings in Birmingham that year, a fact that led the city to be dubbed “Bombingham.”

We learned about the courage of the child crusaders. In 1963, the Black people of Birmingham were scared. They were afraid to miss work to protest; they couldn’t afford to spend time in jail. Movement leaders went into the schools and invited children to participate in marches. These children were trained in the art of non-violence. When they tried to march from the church to City Hall—just on the other side of Kelly Ingraham Park—they were atta

We learned about the courage of the child crusaders. In 1963, the Black people of Birmingham were scared. They were afraid to miss work to protest; they couldn’t afford to spend time in jail. Movement leaders went into the schools and invited children to participate in marches. These children were trained in the art of non-violence. When they tried to march from the church to City Hall—just on the other side of Kelly Ingraham Park—they were atta cked by police dogs and fire hoses. The images of that violence spread throughout the world and galvanized needed attention for the Civil Rights movement.

cked by police dogs and fire hoses. The images of that violence spread throughout the world and galvanized needed attention for the Civil Rights movement.

Later in the evening, we visited a memorial to William Miller. In 1908, Mr. Miller was falsely accused of setting off a bomb during a coal miners’ strike. Miller was abducted from the jail where he was being held, lynched, and hanged from a tree just outside the jail building. His was one of more than 4,000 lynchings that took pace between 1890 and 1940. The plaque telling his story was the first of many such plaques to be erected by the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama.

Later in the evening, we visited a memorial to William Miller. In 1908, Mr. Miller was falsely accused of setting off a bomb during a coal miners’ strike. Miller was abducted from the jail where he was being held, lynched, and hanged from a tree just outside the jail building. His was one of more than 4,000 lynchings that took pace between 1890 and 1940. The plaque telling his story was the first of many such plaques to be erected by the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama.

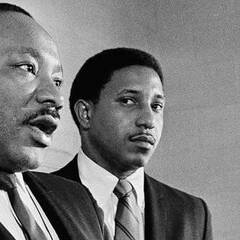

Our group, together with Dr. Bernard LaFayette, outside the Dr. Harris House

Day Three – January 31

Voting rights were the official theme of today’s visit to Selma. Selma, a city where only 2% of eligible Blacks were registered to vote, had been the target for voter registration in early 1965. On March 7, 1965, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., led a what was to be a 54 mile march from Selma to Montgomery to demand action to increase voting rights in Alabama and throughout the country. The group had barely crossed the Edmund Pettis Bridge when they were attacked by officers, troopers, and newly-deputized citizen posses in what came to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” Two days later, on what came to be known as “Turnaround Tuesday,” the group began its march and turned around when they realized they were not going to be able to pass the police barricade. A third march began on March 21, this time protected by 1900 members of the Alabama National Guard, and arrived in Montgomery on March 24. The Voting Rights Act became law on August 6, 1965. History suggests that it was the activities in Selma that made the Voting Rights Act possible.

Our posted theme was voting rights, but the powerful takeaway was the personal stories. We met with Terry Chestnut, son of JL Chestnut, the first black lawyer in Alabama. Mr. Chestnut shared stories about his father’s career as King’s personal attorney, legal advisor for so many Civil Rights Activists, and successful litigant for so many years after that. Terry Chestnut shared a personal account of how, as a 6 ½ year old, he witnessed the attacks of Bloody Sunday from the side of the road. He then led our group on a march across the bridge—a truly powerful experience.

Our posted theme was voting rights, but the powerful takeaway was the personal stories. We met with Terry Chestnut, son of JL Chestnut, the first black lawyer in Alabama. Mr. Chestnut shared stories about his father’s career as King’s personal attorney, legal advisor for so many Civil Rights Activists, and successful litigant for so many years after that. Terry Chestnut shared a personal account of how, as a 6 ½ year old, he witnessed the attacks of Bloody Sunday from the side of the road. He then led our group on a march across the bridge—a truly powerful experience.

On our way back to Montgomery, we stopped at a memorial to Viola Liuzzo. Ms. Liuzzo was a white member of the NAACP from Detroit who had traveled down to Selma, at the request of Dr. King, to join the final march to Montgomery. After the arch, she helped to shuttle other marchers back to their homes in Selma. After bringing her first carload of marchers home, Viola was on her way back to Montgomery when she was run off the road by a car carrying three Klansmen and an undercover FBI agent. Liuzzo was shot right there on the side of the road. Our group joined together in song and prayer at the memorial.

During the day, we also visited Temple Mishkan Israel. Today the synagogue is only 3 members, but one of them, Ronnie Levy, told us the story of this congregation. We toured the historic congregation, which includes stained glass windows of biblical themes, a pipe organ, and straight pews that might be expected in American Protestant worship spaces. Mr. Levy also began to explain the conflicted reactions of Temple members to the events of 1965. This was a difficult time for Jews trying

During the day, we also visited Temple Mishkan Israel. Today the synagogue is only 3 members, but one of them, Ronnie Levy, told us the story of this congregation. We toured the historic congregation, which includes stained glass windows of biblical themes, a pipe organ, and straight pews that might be expected in American Protestant worship spaces. Mr. Levy also began to explain the conflicted reactions of Temple members to the events of 1965. This was a difficult time for Jews trying to fit in as a minority in a deeply racists Christian society. Most members did not participate in the marches. That story was difficult to hear … but it was also very real to experience the complicated reality of the Civil Rights story.

to fit in as a minority in a deeply racists Christian society. Most members did not participate in the marches. That story was difficult to hear … but it was also very real to experience the complicated reality of the Civil Rights story.

I feel grateful to be experiencing this trip with wonderful rabbinic colleagues and other leaders of our Washington Jewish community. I’m looking forward to our visit to Birmingham tomorrow.

Day Two – January 30

It was another long and intense day in Montgomery. If there was a theme to the day, it was the challenges (and joys) of leadership.

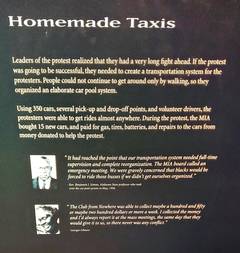

We began the day in the Rosa Parks Museum and Library. We know how Rosa Parks’s courageous stand on December 1, 1955, led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott that ignited the Civil Rights Movement. But we don’t appreciate the incredible leadership that was needed to overcome the challenges of sustaining a boycott for 381 days. The pushback was significant. History views Civil Rights leaders with admiration, but at the time they were considered troublemakers. We learned about the elaborate carpool system they had to devise in order to get people to work each day. Carpoolers couldn’t collect fares, because then they would be driving illegal taxis. Even the search for car insurance – they had to go to Lloyds of London because it was the only company willing to cooperate – was difficult.

We began the day in the Rosa Parks Museum and Library. We know how Rosa Parks’s courageous stand on December 1, 1955, led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott that ignited the Civil Rights Movement. But we don’t appreciate the incredible leadership that was needed to overcome the challenges of sustaining a boycott for 381 days. The pushback was significant. History views Civil Rights leaders with admiration, but at the time they were considered troublemakers. We learned about the elaborate carpool system they had to devise in order to get people to work each day. Carpoolers couldn’t collect fares, because then they would be driving illegal taxis. Even the search for car insurance – they had to go to Lloyds of London because it was the only company willing to cooperate – was difficult.

After the museum, we visited the parsonage where Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., lived when he pastored the Deter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery. We saw the indentation in the front porch, caused by a bomb thrown at the house on January 30, 1956, to try to deter his leadership of the bus boycott. We saw the kitchen where King went after the bombing, where he claimed a vision of God urging him to continue his work. Our guide, Avis Smith, remembered Rev. King from when she was a little girl and he was her pastor. Her expressions of reverence and admiration for her family’s spiritual guide were particularly impactful on our group of rabbis. Leadership is difficult … but those moments of relationship are incredibly inspiring.

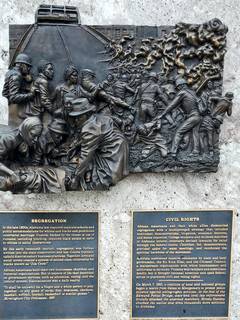

Ms. Smith was honest about some of the ongoing challenges of living as a Black woman today. We walked down the block to the Alabama State House and saw monuments to the Civil War, President Jefferson Davis, the first White House of the Confederacy, all erected between 1890 and 1930, and considered what it means for Black Citizens to see these symbols of White Supremacy on State property. We also visited a series of monuments, erected for Alabama’s bi-centennial in 2019, which told a much more nuanced story of the state.

Ms. Smith was honest about some of the ongoing challenges of living as a Black woman today. We walked down the block to the Alabama State House and saw monuments to the Civil War, President Jefferson Davis, the first White House of the Confederacy, all erected between 1890 and 1930, and considered what it means for Black Citizens to see these symbols of White Supremacy on State property. We also visited a series of monuments, erected for Alabama’s bi-centennial in 2019, which told a much more nuanced story of the state.

In the evening, we visited with Rabbi Scott Kramer of Congregation Agudath Israel Etz Ahayim. He described the Jewish community of Montgomery. It’s an aging community; many of the members of his congregation remember the bus boycott, as well as the divisions that event created within the Jewish community. The Jewish community in Montgomery is dwindling, and it is unclear that it will continue to support its two synagogues (one Reform, one Conservative) for too much longer. I felt a personal connection to this part of the tour because I considered accepting a job at that congregation, in 2002; I decided to come to B’nai Israel instead.

After dinner, I enjoyed some time “talking shop” with my colleagues. Tomorrow, we are visiting Selma.

Day One – January 29

After months of anticipation, our group arrived in Montgomery, AL, for a five-day journey into the history of racism in our country, exploring stories that were never told and considering lessons to be learned and taught. Our group of 23 is mostly rabbis, along with several non-rabbinic agency heads. Our group represents all of the American Jewish movements, which is significant because we represent a range of religious approaches and diverse political persuasions. I am grateful to the Jewish Federation of greater Washington for putting this experience together.

After months of anticipation, our group arrived in Montgomery, AL, for a five-day journey into the history of racism in our country, exploring stories that were never told and considering lessons to be learned and taught. Our group of 23 is mostly rabbis, along with several non-rabbinic agency heads. Our group represents all of the American Jewish movements, which is significant because we represent a range of religious approaches and diverse political persuasions. I am grateful to the Jewish Federation of greater Washington for putting this experience together.

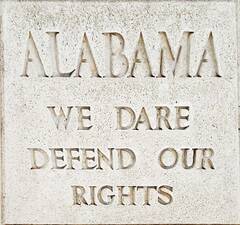

One of the themes of our trip is stories, told and untold. After meeting in the Atlanta Airport, our group headed down I-85 towards Montgomery. We stopped at a Rest Area shortly after crossing into Alabama. Outside the restrooms, we gathered around a monument, which read: “Alabama: We dare defend our rights.” The slogan dates back to a 19th-century land dispute between the State of Alabama and the Creek Nation. In the lead-up to the Civil War, the slogan came to refer to the state’s “right” to hold slaves. During the Civil Rights Era, George Wallace fought to defend the “right” to keep schools segregated. In all three cases, the “we” referred only to the state’s White population.

One of the themes of our trip is stories, told and untold. After meeting in the Atlanta Airport, our group headed down I-85 towards Montgomery. We stopped at a Rest Area shortly after crossing into Alabama. Outside the restrooms, we gathered around a monument, which read: “Alabama: We dare defend our rights.” The slogan dates back to a 19th-century land dispute between the State of Alabama and the Creek Nation. In the lead-up to the Civil War, the slogan came to refer to the state’s “right” to hold slaves. During the Civil Rights Era, George Wallace fought to defend the “right” to keep schools segregated. In all three cases, the “we” referred only to the state’s White population.

In Montgomery, we visited The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. This museum, a project of the Equal Justice Initiative that opened in 2021, charted a history of injustice that began in the 17th-century with the slave trade and continued through an era of lynching to an era of mass-incarceration. The power of the museum was in the individual names and stories that were told. We were struck by the extent to which racism and dehumanization pervaded society. Lynchings were conducted in the open and few people were ever punished. We were left to ask how the legacy of such institutional racism continues to impact the lives of American citizens today.

This first day was intense, and it produced more questions than answers. I look forward to continuing to explore, process …. and eventually invite others to the conversation as well.

Thu, April 18 2024

10 Nisan 5784

Livestream

Shabbat Services

Friday at 6:15 PM

Saturday at 9:00 AM

the latest

announcements

Lessans Talmud Torah registration for 2024–2025 is open!

Registering early just got sweeter. Learn more about our program and registration raffle.

B'nai Israel Schilit Nursery School 2024-2025 Program Registration is now OPEN - OPEN HOUSE ON APRIL 18!

Our award-winning school can't wait to meet your family. Very limited spaces remain. Learn more. Click here to learn more about our Truck Day Open House on April 18.

Visit Our Judaica Shop for all of Your Passover Needs

For shop hours, click here.

B'nai Israel First Synagogue in North America to Install RightHear, supporting those who are blind or low vision.

Read our press release here.

NEW Resource: Fighting Antisemitism

Raise Awareness, Educate, and Act to stop antisemitism. Learn more.

Our 2023-2024 Hineini Annual Campaign is Under Way

B'nai Israel is "Here for YOU". Support us today.

Join Our Shabbat Morning Livestream

Click here to access.

Explore Our Exciting Adult Education Offerings

Learn more here.

weekday services

Sunday | 9:00 AM & 8:00 PM

Monday–Thursday | 7:15 AM & 8:00 PM

Friday | 7:15 AM

*Service times vary on holidays.

Click here for access information.

shabbat services

Friday | 6:15 PM (7:00 PM during Summer)

Saturday | 9:00 AM & 12:30 PM (Minha)

Click here for access information.

inclement weather policy

Click here for information.